Monthly Archives: October 2024

‘They just took the baby away’: Family speaks out in church-run homes scandal

‘They just took the baby away’: Family speaks out in church-run homes scandal

- Wednesday 16 October 2024 at 10:27pm

A family has come forward following an ITV News investigation into cruelty and abuse at ex church run mother and baby homes, Social Affairs Correspondent Sarah Corker reports

Further allegations of abuse and neglect at a former church-run mother and baby home in Cumbria have emerged, following an ITV News investigation. Earlier this year we revealed that 45 babies who had died at St Monica’s home – in Kendal were buried in an unmarked grave in the town’s cemetery.

St Monica’s was one of hundreds of homes for unmarried mothers across England.

Between 1949 and the mid-1970s, an estimated 200,000 women were sent away to homes run by churches and the state where they were pressured and coerced in to give up their babies for adoption. Other infants died through poor care.

Since our first report aired in July, the family of one of those children has come forward and told ITV News that their mother was lied to about the fate of her baby daughter, Faith, and was never told where she was buried.

Norah Everard was in her 80s, and dying from cancer, when she told her family for the first time about the trauma she’d endured decades earlier as a teenager in 1941.

Pregnant and unmarried, she was sent away to St Monica’s, which was run by the Diocese of Carlisle, to have her baby.

Norah’s son Bob Chubb recounted the details that his late mother shared with him and his wife Carole about the “cruel” home.

“We were all round the table one Christmas, and she said ‘I’ve got something important to tell you both. Bob you weren’t my first born’, and then she told me about being raped as a young school girl, going to St Monica’s in Kendal to have the baby, and the baby was stillborn, called Faith,” Bob told ITV News.

Burial records seen by ITV News suggest that Norah was lied to, they show that Faith wasn’t stillborn and that she had lived for 12 hours and was later buried in an unmarked grave at Parkside Cemetery in Kendal – one of the 45 babies who were buried in secrecy.

If you’d like to share your story please get in touch with Sarah on the following email: Investigations@itv.com

“I don’t think she was told the truth. I think some terrible things went on,” Mr Chubb said. Carole Chubb, Bob’s wife, said: “It really really disgusts me. They just took the baby away and said the baby’s dead and that’s it. Did they even given her any milk? Would she have survived? “Norah told me it was cruel place, they made the women scrub floors when they were heavily pregnant and they were refused pain relief in labour as a punishment.”

Bob and Carole share their family’s story and concerns about how babies were treated

Concerns have been raised by other families about the poor care of sick and premature babies at the home in the decades after the war, while official documents from the archives paint a disturbing picture of neglect, cruelty and suffering inside St Monica’s. Bob revealed that he too was born prematurely at the same home in the late 1940s, and feels ‘lucky’ that he survived.

The acting Bishop of Carlisle Rt Rev Rob Saner-Haigh described what had happened to Norah and her daughter as ‘wrong’ and said he was ‘really sorry’ for the way women and children had been treated.

The acting Bishop of Carlisle Rt Rev Rob Saner-Haigh answers questions from ITV News

Since allegations of abuse first emerged, 20 people with a connection to St Monica’s have contacted the Diocese requesting access to their family records. “The Church of England should do all it can to support people who have lived with the trauma. We need to listen and give them a choice in decision making so they can tell us what they need and as an organisation we show them the love and dignity that they weren’t shown before,” he said.

The family of another baby, Stephen Holt, who died aged 3 months old at the home in 1964, are now campaigning for a permanent memorial to the 45 babies.

It was years later when baby Stephen’s mother Judith Hindley first told her husband, also called Stephen, of the abuse she endured at the ‘draconian’ home in the late 1960s. “Judith was 17 at the time and told me how she was forced to clean floors and kitchens while heavily pregnant. They were being punished,” he said. “Her son Stephen was born with disabilities and needed to go to hospital, but he was cruelly denied proper medical care and died 11 weeks later.” She never recovered from that trauma and in 2006, Judith took her own life close to the cemetery where her baby is buried.

Stephen Hindley explains what happened to his wife Judith at St Monica’s and why he is campaigning for a memorial

Cumbria Police has confirmed it is still investigating allegations of historic abuse at St Monica’s and said it “would welcome any new information which would assist officers…following concerns raised in relation to these premises”. Westmorland and Furness District Council which owns the cemetery where the graves are located said: “We are currently exploring options and reaching out to others who may wish to be involved or consulted on the possibility of marking the unmarked graves at Parkside Road cemetery, Kendal relating to the former St Monica’s Maternity home.”

Department for Education spokesperson said: “We have the deepest sympathy with all of those who are affected, the practice was abhorrent and should never have taken place.

“While we will not be able to quickly make every change we would like, we will look at whether there is any more we could do to support those affected.”

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-gloucestershire-68629466

Couple adopted vulnerable children to abuse

- Published

22 March

Delay and frustration in adoption law’s first year

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp3dx01v8x8o

Delay and frustration in adoption law’s first year

At a glance

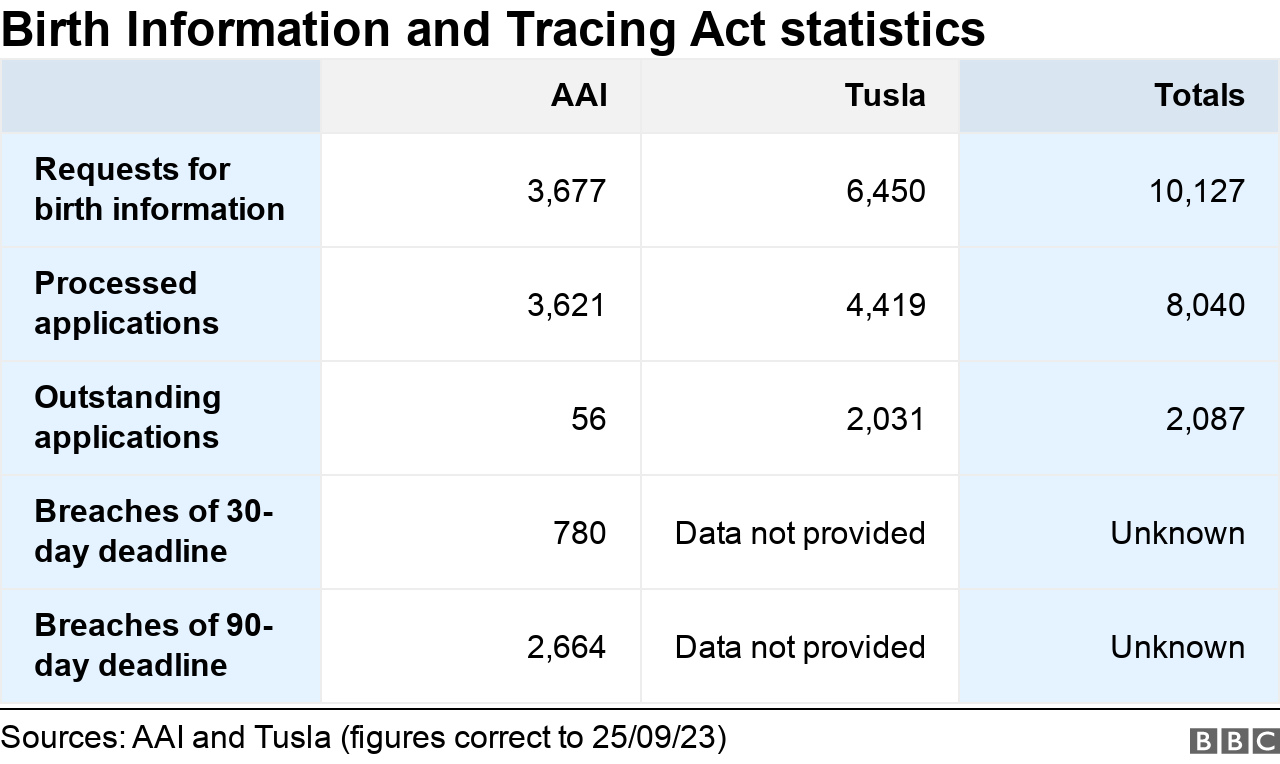

- More than 10,000 requests for adoptees’ birth records have been submitted during the first year of a new Irish law

- The authorities struggled to meet demand and missed legal deadlines

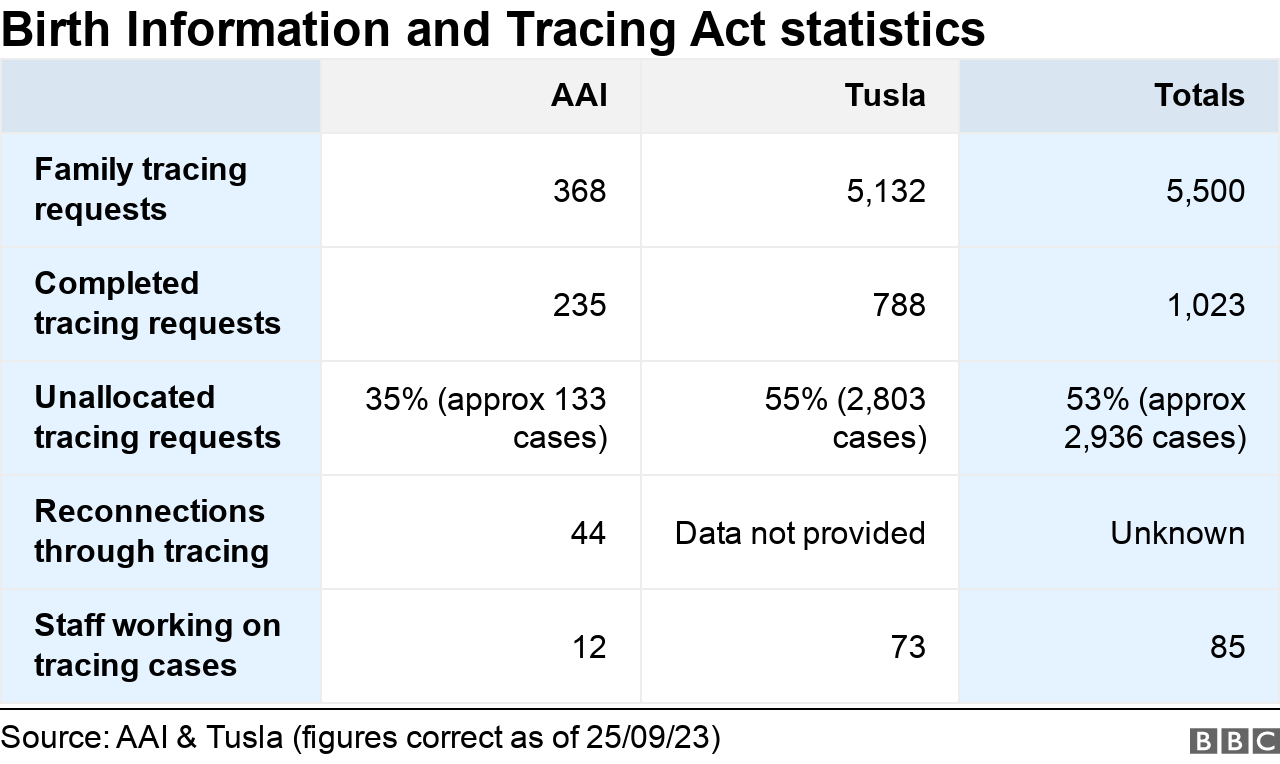

- A total of 5,500 requests were made to use a new family tracing service

- More than half (53%) of tracing requests are yet to be allocated to staff

Eimear Flanagan

BBC News NI

- Published3 October 2023

An Irish law that gave adopted people the right to access their birth records has led to more than 10,000 applications during its first year of operation.

The Birth Information and Tracing Act, external was designed to end much of the secrecy embedded in Ireland’s 70-year-old adoption system.

But for many adoptees waiting decades for answers about their early lives, the new procedures meant delays and frustration.

The legislation created a new family tracing service and throughout the year 5,500 requests to find relatives were submitted.

However, due to the complexity of some searches, 53% of tracing requests are yet to be allocated to staff.

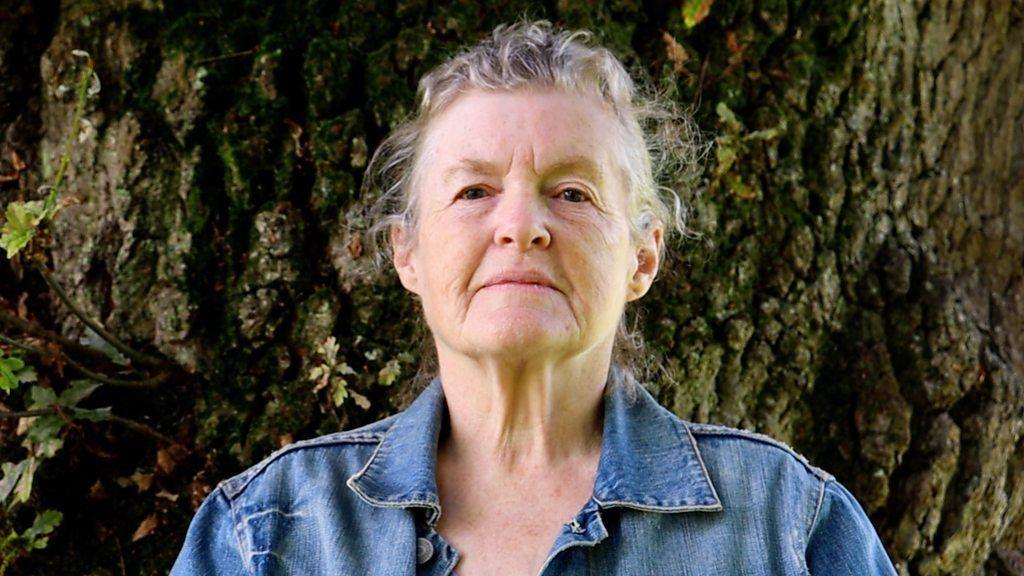

“I am relying on a system that is working at a snail’s pace,” said Linda Southern, who is searching for her birth parents.

The 48-year-old Dubliner was adopted in 1975 at six weeks of age.

She spent her first 47 years not knowing her birth name nor the names of her mother and father.

That is because until 3 October 2022, Irish adoptees had no automatic right to see their own birth certificates, nor to know their biological parents’ identities.

The new law was supposed to give adoptees access to birth records within 30 days, or 90 days in complex cases.

Two organisations tasked with releasing records struggled to handle an early surge of applications.

The Adoption Authority of Ireland (AAI) and child and family agency Tusla both missed statutory deadlines.

“The initial surge led to wait times which would be frustrating and which we regret,” said AAI interim chief executive Colm O’Leary.

“When you’re starting off a process and you’re learning that records are held across various sources, it takes time to become familiar with all of the record types,” he explained.

A Tusla spokeswoman said “a significant portion of the applications are classified as complex which means they require more time”.

But adoptees argue authorities should have been better prepared.

“Surely, state bodies would have had a basic idea of the number of adoptees who would want to at least get their birth information,” said Ms Southern.

After initial delays, she received her own documents which – for the first time – revealed her original name and parents’ names.

However, she still needs help finding her biological family and spent the past year waiting for news.

“I don’t know if they will ever trace my birth mother or not.

“If they can’t, I should be told,” she said.

“They should have presumed the majority would want to trace – better to presume that too many people would wish to trace birth families than too few.”

‘Belfast baby’

Loraine Jackson had hoped her birth files might shed some light on her cross-border adoption.

She grew up in Dublin, with barely any information about her birth.

But in her early 40s, she found out she was actually a native of the United Kingdom, having been born to a single mother in Belfast in 1948.

Her parents died years before she could trace them.

When she spoke to BBC News NI last year, she expressed hope her files might reveal how or why she was taken across the border for adoption.

After months of waiting, a “fat package” arrived in the post which included an unredacted version of her adoption agreement.

For the first time, she saw her relatives’ signatures and finally found out who authorised her adoption.

“My birth mother had not been present at the signing. Her sister signed for her,” Ms Jackson explained.

She also expected her files would contain information about the standard of care she received in Bethany children’s home in Dublin.

But apart from a photocopy of her name in Bethany’s admission book, she was disappointed.

“The information just didn’t seem to be there. Whether records were not kept as well in those days, I don’t know.”

Although left with many unanswered questions, her maternal aunt’s role in her adoption was new information to her.

“It was definitely worthwhile doing, and I’d advise anyone who hasn’t applied yet to go for it.”

AAI staff received a wide range of feedback from adoptees about their birth files – from delight to disappointment to disbelief.

“A lot of people have said: ‘Is that it? Is there nothing else?'” Mr O’Leary said.

He acknowledged some adoptees were dismayed to learn that nothing more exists on file than details they already knew.

Others have received heavily censored documents.

“Sometimes the authority gets records that are already redacted prior to us getting them… we cannot unredact it,” Mr O’Leary explained.

He also said AAI staff can apply redactions themselves, in cases where personal information refers to a third party.

However, he added applicants can request a review if they believe files were “inappropriately redacted”.

The interim chief executive acknowledged the AAI’s 12 social workers have “significant” tracing workloads.

But he said tracing “is not a linear process” and adoptees often pause the search themselves to digest new information.

“You’re dealing with a very emotive situation,” Mr O’Leary said.

“People may initiate a trace, thinking that their birth mother would want to hear from them, and they have to take on board that the birth mother does not want contact.”

But the new law produced positive outcomes too – the AAI’s tracing service has facilitated 44 family reunions.

“Sometimes I’ll go to the kitchen and I’ll see a social worker taking out the fancy crockery and making tea” Mr O’Leary said.

“They’re bringing it into a room where a family is being reunited.”

He added that when staff help connect families “there is a sense of success, and of delivering on the legislation”.

The AAI’s backlog of birth record applications is almost cleared and by last week, just 56 were outstanding.

Tusla has a much larger backlog which it expects to clear by June 2024.

It said from1 September, all new applications are being processed “within statutory timelines”.

If you are affected by the issues raised in this story, help and support can be found at BBC Action Line.

Mother and baby homes: NI-born survivor ‘abandoned again’

Mother and baby homes: NI-born survivor ‘abandoned again’

Published 18 March

By Eimear Flanagan BBC News NI

A woman from Dublin, born into a mother and baby home in Northern Ireland, has said she feels “abandoned again” because she is excluded from a new compensation scheme. Sinead Buckley was born in 1972 to an unmarried woman from the Republic of Ireland. At that time her mother, Eileen, was living in Marianvale in Newry. A midwife in Dublin, Eileen came north because of the fear and stigma associated with being a single mother. Marianvale was one of a network of institutions across the island of Ireland which housed unmarried women and their babies at a time when pregnancy outside marriage was viewed as scandalous. After the birth in Newry’s Daisy Hill Hospital, an adoption agency in the Republic arranged for Eileen’s baby to be adopted by a family in Dublin. Ms Buckley grew up and still lives in Dublin, but never got to meet her birth mother. Eileen died during a Covid lockdown which meant she endured the heartbreak of watching her mother’s funeral over the internet. This week, the Republic of Ireland will open an €800m (£684m) redress scheme, external for survivors of its own mother and baby homes. Ms Buckley is one of thousands of Irish adoptees who will not qualify, despite her decades-long battle with the Irish state to access her birth identity and family medical history. “I grew up with a sense of rejection and abandonment and I feel like I’ve just been completely abandoned again,” she told BBC News NI.

“I used to be proud to be Irish, I’m not anymore. I’m not Irish what I am?”

Ireland’s Department of Children said that Marianvale was outside the Republic’s jurisdiction, adding there were “processes ongoing in Northern Ireland to respond to these legacy issues”.

But as a Dubliner, born to parents from the Republic, Ms Buckley said she cannot understand why she is excluded from the Irish redress scheme “because I was born a few miles over the border and adopted back here”.

Who qualifies for compensation?

Under the rules, mothers who spent even one night in an eligible institution in the Republic will receive compensation. Payments start at €5,000 (£4,275) and rise incrementally based on length of stay, external. But former child residents only qualify if they spent six months or more in homes. Marianvale is not on the list of eligible institutions, but even if it was, Ms Buckley would still not be entitled to compensation because it appears she was resident for less than six months. “I wish someone would explain the six-month thing to me because we’ve suffered through life,” she said.

“There’s absolutely no humanity in this decision.”

She added she paid Irish taxes all her life and now the Irish state “isn’t recognising me”. “For me it’s not about the money, it’s about the principle,” she said. “I want to be vindicated.”

‘Where do I belong?’

Adoption records show her mother was engaged to a Tipperary man when she became pregnant, but Eileen’s family opposed her relationship. When she entered Marianvale, her fiancé was not even told he was about to become a father. The adoption was arranged by Cunamh, formerly known as the Catholic Protection and Rescue Society of Ireland. “If the adoption was arranged from counties in the south and agencies in the south run by convents and nuns in the south and women from the south were in there and the children were adopted back into the south it’s just a loophole to get out of paying anybody money,” Ms Buckley said.

Border babies

Her cross-border journey was not unique. A recent report into Northern Ireland’s mother and baby homes, external calculated that more than 550 babies were moved to the Republic between 1930 and 1990. “Here in the north, the campaigners have been calling for their public inquiry and redress for more than a decade,” said solicitor Claire McKeegan, who acts on behalf of survivors of institutional abuse in Northern Ireland.

In 2021, Stormont’s leaders agreed to hold a public inquiry into mother and baby homes, Magdalene laundries and workhouses north of the border. But two and a half years on, that inquiry is still to be legally established. “Obviously with the collapse of Stormont, the legislation hasn’t happened for them and many survivors and victims are no longer with us,” Ms McKeegan said.

The solicitor is due to meet First Minister Michelle O’Neill about the issue next month and said the message from survivors will be: “It must be done and it must be done now.”

For Ms Buckley though, it was the Republic’s secretive adoption system which she had to fight all her life. As a teenager she suffered serious health issues and baffled doctors ran lots of tests because they could not access her family medical records. “My mother told me that at one stage they thought it was leukaemia and that the doctors had been trying to ring the adoption agency just to try and get some history. They were like: ‘This girl is really sick, we need to know.’ And they were just met with closed doors.”

Aged 43, Ms Buckley was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS), a condition she later found out runs in her birth family. She believes she missed out on earlier diagnosis and treatment due to her lack of rights to birth information when she was a teenager. A new Irish law came into force in 2022 which gave all adoptees rights to access their original birth certificate and family medical history, but adoptees complain of long delays with the new system. How many survivors get compensation?

It has been estimated there are about 58,200 people still alive who spent time in the Republic’s mother and baby homes and county homes (institutions which succeeded workhouses). The Department of Children confirmed its redress scheme will “provide financial payments to an estimated 34,000 people”.

But that means just over 40% of survivors some 24,000 people cannot apply because of the six-month rule. Awarding payments and medical benefits to all surviving residents would have doubled the cost of the scheme. “The exclusions are vast and it really is extremely unfair,” said Dr Maeve O’Rourke.

The human rights lecturer recently helped design the framework for investigating homes in Northern Ireland. Dr O’Rourke argued the Republic’s 2015-2021 mother and baby homes investigation, external was too narrowly focused and has resulted in a restricted redress scheme. She said there should have been a wider investigation into adoption across all of society, including the role of adoption agencies, maternity hospitals, “forced family separations” and illegal birth registrations. “Unfortunately, and perhaps to limit its ultimate financial liability, the Irish government insisted that it would be limited to mother and baby institutions and a sample of county homes,” she added.

Ms Buckley took part in a 2021 public consultation, external in which survivors and interested parties gave views on the design of the redress scheme. Most survivors stressed loss of the mother/child bond was the most important factor that required redress, not the time spent in homes. Ms Buckley shared her own experience during the consultation but was shocked when she realised Marianvale residents would not be part of the settlement. “I couldn’t stop crying. We bared our souls at that thing, you know? We told them how this has affected us mentally,” she said.

“For saving a few quid, we’re just collateral damage.”