birth

My baby died at birth and I wasn’t even allowed to hold him. Then, 42 years later, he emailed me out of the blue… and I learned the horrific truth

My baby died at birth and I wasn’t even allowed to hold him. Then, 42 years later, he emailed me out of the blue… and I learned the horrific truth

By DIANE SHEEHAN

Published: 01:47, 5 September 2025 | Updated: 08:12, 5 September 2025

As I opened the email, I was transported back more than 40 years. Back to a stark hospital room and a cold stainless-steel trolley where I lay, naked, bleeding, terrified and alone.

Violent tremors shook my body as the trauma of that terrible day in September 1976 came flooding back. Shameful memories I’d been so careful to keep locked away were suddenly screaming for attention. I read the words on my phone again … and again. This couldn’t be true, it just couldn’t.

A 42-year-old man called Simon had written to me out of the blue, to say he believed I could be his mother. He’d been adopted at birth and the dates and location certainly tallied; I had indeed had a baby that day, in secret, as a woefully naïve, unmarried 21-year-old.

But Simon couldn’t be my son, because my baby had died. The midwives had whisked it away, without even telling me if I’d had a boy or a girl, before returning to tell me, dispassionately, that the baby was dead.

There were no comforting words, no ‘sorry for your loss’. To everyone at the hospital, I was nothing short of a disgrace and my baby’s death just punishment for my terrible sin.

And so, for four decades, I’d not spoken a word about it: not to my family or friends – not even to my husband and two children. I swallowed my grief and shame, but it never left me.

But could this stranger be telling the truth? Had my baby survived?

With trembling fingers, I opened the photos Simon had included with his message.

Diane Sheehan gave birth in September 1976 but was told her baby had died. She wasn’t able to hold him

There I saw one of his daughter: a small, smiling girl, with my exact dark blonde curls and hazel eyes. It honestly felt like I was looking at a picture of myself as a child.

In that moment, my whole world turned upside down. Forty-two years after leaving hospital with nothing but a broken heart and buried trauma, I was finally on my way to learning the shocking truth.

Like thousands of unmarried mothers across the world, I’d been a victim of a heinous scandal. Such was the shame of having a baby out of wedlock back then, that up until the late 1970s thousands of children were adopted against their mother’s wishes.

In my case, the authorities went one step further by lying to me that my baby had died, so I didn’t even get a chance to object.

Of course, no statistics exist citing how many poor young girls were victims of this particularly cruel crime. If, like me, they’d kept their pregnancy secret, possibly hundreds went to their graves never knowing their child had lived.

Although I count myself as one of the lucky ones as I eventually discovered the truth, at the age of 63, my fury was intense.

It was more than anger; it was a sense of total disempowerment. These strangers had taken control of my life, because they thought that they knew better, and treated me like rubbish to be swept away and forgotten.

I was born in 1955 to a strict Catholic family, the eldest of five children, and raised in Wellington, New Zealand.

Diane in her 20s. She had her baby in secret as an unmarried 21-year-old

We went to a religious school and church three times a week. Our ‘sex education’ – if you can call it that – consisted of quite frankly ridiculous ‘advice’ such as never to sit on a bus seat after a boy, as you could get pregnant.

When I left home at 19 to work in a pub in Sydney, Australia, mum had slipped me a booklet about anatomy under the bathroom door, but even then I had only the sketchiest ideas about biology and how babies were made.

From Sydney, I got an au pair job in Canada, where I lived an ideal life, riding horses on the family’s land. And it was here, aged 20, that I fell in love with Jason, a handsome man ten years my senior, who lived on a nearby farm.

Of course, when we began having sex, we didn’t use contraception. Utterly naïve, and hopelessly in love, it just didn’t occur to me.

When Jason got a job in California I went to visit him for a weekend but missed my flight home. When I returned, my employer was furious and sacked me on the spot. No job meant no visa, so I had to return to New Zealand.

I was devastated. By then Jason was travelling and, while I considered writing to his old farm in the hope they might be able to pass on a message, since they didn’t know about our relationship, I eventually decided not to.

A month later I got another job in Sydney, at a horse farm run by a Catholic doctor, Mark, and his wife, Alice. When I started feeling nauseous, I initially put it down to heartbreak. Yet I’d seen enough on the farm to understand what my swelling stomach signalled.

Denial and guilt are a powerful combination, however, so I hid in baggy dungarees and worked from sunrise to sunset, deliberately leaving myself too exhausted to think about the future.

Diane ploughed all her energy into work, going on to study veterinary science at university and qualifying as a vet

My feelings of shame were so intense I didn’t consider telling anyone – not my family, or even Jason. But there was only so long I could maintain my state of denial.

One night in September 1976, when I was 21, my contractions started. By morning, the pain was so intense, I staggered to the main house begging for help, saying I had dreadful stomach-ache.

Alice drove me to the local doctor. I heard him say, ‘oh my God’ as he removed my overalls, and I saw the shock – and anger – on Alice’s face when the truth hit her.

She refused to even go with me to the hospital.

The same attitude greeted me on the labour ward, where one glance at my ringless left hand told the medical staff everything they needed to know.

I’ve managed to block out most of the details of the birth: the agony, the terror and the strange silence that descended as my baby was bundled up and spirited away in a stranger’s arms.

I never heard him cry. I never even saw his face. I was left naked, bleeding, freezing and sobbing on the hospital trolley.

What happened next is still a horrible blur; I can’t remember the specific words used, but I know a woman returned to tell me my baby hadn’t survived.

Diane never heard her baby cry and didn’t even see his face

At that moment, I shut down, without the strength to ask any questions, telling myself I deserved this.

The next thing I remember, some paperwork was thrust into my hand, and a cold voice told me I couldn’t leave until I’d signed the discharge papers. Like a robot I did what I was told.

I was in turmoil, and without anyone to comfort me. Nobody knew about my pregnancy except Alice and Mark, and their house was the only place I had to go.

I can’t recall how I got there, I just remember walking into the house and no one uttered a word. They didn’t ask about the baby, or what had happened – nothing.

It was such a dark time. But how could I grieve a child I’d tried so hard to pretend I’d never carried?

I did the only thing I could think of; I put it all – Jason, the pregnancy, the baby – in a mental box and slammed it shut.

Later that year, when a visiting vet offered me a job elsewhere in Sydney, I left Alice and Mark’s house without saying goodbye.

A new Diane had replaced the naïve, trusting girl who’d first left home at 19 – a young woman hardened to the world and determined never to be made to feel so powerless again.

I ploughed all my energy into work, going on to study veterinary science at university and qualifying as a vet.

In 1983, I met Ian, another student. He was my first sexual partner since Jason but, having now abandoned my faith, our relationship felt fun and exciting – free from the guilt I’d previously felt.

We went on to marry in 1987, yet I never came close to sharing my terrible secret with him; while he might have been supportive, I didn’t want to risk ruining my fresh start by opening Pandora’s box.

In 1991, our daughter Sarah was born. The pregnancy was a world away from my first one; now, everyone was so happy for me, and I felt loved and respected.

As for the birth itself, it was night and day compared with my previous labour.

And yet, after Sarah was taken to be weighed and measured, I didn’t automatically hold out my arms to get her back. I was frozen. The nurse had to gently ask, ‘Do you want to hold your baby?’

When I did, the wave of love I felt was incredible. Cradling my beautiful daughter in my arms, it hit me: this one I get to keep.

I promised her I wouldn’t let a day go by without me telling her how much I loved her.

I adored motherhood, and at times watching Sarah I’d find myself thinking ‘What if …?’

Yet I’d quickly push those thoughts away.

When our son Daniel was born two years later, I felt the same fierce love of a woman who knows what it’s like to not bring a baby home. Somehow, 25 years passed. The children grew into happy, healthy adults and, although my marriage didn’t last, I was living a good life, filled with love.

Then one evening in December 2018, I’d been out for dinner with Daniel and on my return noticed an email on my phone from an unknown address.

It was long, and at first only certain phrases jumped out at me. That Simon, the writer, had been adopted at birth, from the same hospital I’d attended, and had recently taken a DNA test, which had led him, via a long, convoluted path, to me.

He’d found a picture of me online and had immediately recognised a similarity to his own daughter, then three.

While some people might have thought it was a mistake, or a scam, when I saw the picture of Simon himself, I was left in no doubt. He was the image of Jason. I knew, just knew, that this 42-year-old man was my first-born child, and that the hospital authorities had lied to me.

Those ‘discharge’ papers at the hospital? They must have been adoption papers. The cruelty took my breath away.

I had no idea where to turn to or what to do.

Frantically googling for answers, I found The Benevolent Society, which supports people affected by adoption.

The very next day, I found myself sitting in their office with a counsellor.

For the first time in 42 years, I talked about my past. Everything I’d bottled up for decades, all the pain, fear, guilt and shame, came pouring out – as well as my new-found anger.

The counsellor told me there had been thousands of forced adoptions in Australia in the past and, shockingly, telling unmarried mothers their babies had died wasn’t uncommon.

With her help I was able to sit down and write a reply to Simon a few days later.

‘There’s no easy way to say this,’ I wrote. ‘But when you were born, I was told you’d died.’

I tried to explain the impact that losing him had on my life, and told him about Sarah and Daniel, his half-sister and brother.

Without my counsellor I’d never have made it through; my emotions were in free-fall. I was grappling with exhaustion and guilt at hiding this bombshell from Sarah and Daniel, as well as the awful fear that when they did discover it, they’d judge me.

I knew I’d have to tell them at some point, but I needed to meet Simon first, to get my facts straight.

In follow-up emails, Simon explained he’d been adopted at birth by a lovely couple who adored him. Though he always knew he was adopted, he’d had a wonderful childhood.

After becoming a father himself he decided he wanted to find his birth parents, and he’d registered his DNA on an ancestry website, which led him to Jason’s family in Canada.

Jason had recently died, but a relative remembered him mentioning his old girlfriend Diane in Australia, and he’d managed to trace me. When he did, he realised his ancestry results had linked him to some of my relatives too.

Of course, Simon was devastated to learn about the terrible circumstances of his birth. Like me, the sheer cruelty of it astounded him.

His adoptive parents had been kept in the dark too; they’d been told I had chosen to give Simon up but wanted him to be raised by a Catholic family, and for years they’d even sent me letters and photos showing his progress to an address they’d been given. Who knows where they ended up.

The next month I flew two hours from my home in Brisbane to meet Simon.

I was almost hyperventilating with fear. Would blood be enough to bring us together, or would Simon decide he didn’t want me in his life after all? And what would all this mean for Sarah and Daniel?

Then suddenly I was walking through arrivals and saw him, holding a bunch of white flowers. All my fears flew away, and I fell sobbing into his arms – the first time I’d ever held him. He didn’t feel like a stranger at all.

Our conversation – about his family and mine – was warm and easy.

I couldn’t stop staring at him, unable to believe I could reach across the table and touch him. It felt impossible, yet wonderful.

It was hard to say goodbye the next day, but there was one huge hurdle I needed to clear: I had to tell Sarah and Daniel my secret.

Two days later, I invited them over for a dinner, shaking with nerves as we sat down.

Hearing my shocking story, they were incredible; hurt and horrified for me, yet excited to meet their new half-brother.

My relief was indescribable; I fell asleep with a smile on my face for the first time in decades. It was only after it lifted that I realised the true weight of what I’d been carrying all these years.

A few weeks later, we were all sitting in a busy restaurant in Brisbane, sharing food and laughing. Looking around at my three children was overwhelming, and I felt a sense of peace that had once seemed impossible.

There were still more emotional moments to come, like telling my siblings and seeing their shock and sadness, though they were all supportive. My parents had died years before.

In 2019, a year after Simon’s email, I met his adoptive parents. Though what happened at his birth is so sad, I’m glad he found such a loving family.

I investigated pursuing the matter with the hospital where I’d given birth, but was told the buildings had been demolished and the records destroyed.

I decided not to pour my energy into a fight I probably wouldn’t win, and I refused to let bitterness consume me. Instead, I chose peace, to live for now and spend the time I do have with my incredible family.

It isn’t always easy. The anguish of those lost years, and the love I could have given Simon, is a wound that will never heal.

Still, our relationship is wonderful, comfortable and peaceful. We see each other every month and talk or text three times a week.

I’m so proud of the kind, caring person, and amazing father, he is – and the incredible bond we have built against all odds.

- Names have been changed

- As told to Kate Graham

Reflection of adoption

It’s coming up for the most hated time of the year for me. It will be 44 years on the 3rd August that my son was born and it doesn’t get any easier. I shouldn’t let it get to me so much yet it still does and I still can’t talk about it either. It probably comes down to I was expected to carry on as normal as if nothing had happened.

I can still remember my son being born as is it was a recent event. There wasn’t anybody to celebrate with and my tears were of pain and sadness not happiness. I insisted on seeing him and that was the only time I felt happy knowing how beautiful he was. At the same time I knew deep down that this was one battle I wouldn’t win and I wouldn’t raise him.

‘We love our adopted children… but after years of violent attacks we had no choice but to put them back in care’: Shattered parents reveal why so many adoptions fail to HELEN CARROLL

‘We love our adopted children… but after years of violent attacks we had no choice but to put them back in care’: Shattered parents reveal why so many adoptions fail to HELEN CARROLL

By HELEN CARROLL FOR THE DAILY MAIL

Published: 01:58, 29 November 2024 | Updated: 16:13, 29 November 2024

Having met while working at a children’s charity, Naomi and Martin were aware of the challenges of adopting children who have had a difficult start in life.

They also believed that, given their experience, if any couple had the skills needed to provide the right mix of love, nurturing and guidance required, it was them. However, 12 years after adopting two young children – years in which the parents were beaten and abused so violently they regularly had to call the police, and both suffered nervous breakdowns – the children, now aged 15 and 16, are back in care.

They lay the blame for this heartbreaking situation squarely on their local authority which, they say – due to a lack of funding and a ‘pass the buck’ culture – totally abandoned them to their fate.

Says Naomi, 45: ‘We did our best, but the children desperately needed professional help which, once they were officially adopted by us, was almost impossible to access.

‘I’m not saying that I thought we’d ‘save’ them, but I, naively, believed that with love, stability and permanence we were providing an environment in which any difficulties that arose could be worked through.

‘We never bargained for being kicked, hit, spat at and verbally abused – Martin is deaf in one ear after one particularly vicious punch from our son – and certainly not for the relationship with our children to completely break down.’

It’s notable, and poignantly sad, that this couple still refer to the brother and sister, whom they welcomed into their home aged two and three, as ‘theirs’. They love them and feel guilty about what happened.

They’d gone into the adoption process longing for a forever happy family, after learning they were unable to have children themselves.

Adoptive parents have been left traumatised, their marriages wrecked – and even driven to taking their own lives – by a system incapable of supporting them, writes Helen Carroll

It’s a tragedy shared by hundreds of adoptive parents across the UK, who’ve been left traumatised, their marriages wrecked – and even, in extreme cases, driven to taking their own lives – by a system woefully incapable of supporting them.

One support group, PATCH (Passionate Adopters Targeting Change with Hope), which has 700 members, is campaigning for systemic change to address this ‘crisis’. Most members share the same grievance: that children are almost always removed from their birth parents due to significant abuse or neglect, which often begins during pregnancy, where they are exposed to drugs and alcohol. This leaves the children with symptoms of extreme trauma.

However, when behavioural issues manifest post-adoption – some of which can be genetic – the adoptive parents are left to fend alone and, ultimately, blamed when the situation becomes unmanageable.

According to figures from Adoption UK, 65 per cent of adoptive parents experience violence or aggression at the hands of their children. And, based on responses to the charity’s annual survey, the number of adopted children leaving the family home ‘prematurely’ is rising, from three per cent in 2021, to seven per cent in 2023.

‘There’s a common, but false, belief that trauma is healed through love, and therefore adoption is the happy ever after, which any psychologist or psychotherapist will attest, it is not,’ says Fiona Wells, who runs PATCH and is herself a social worker, working in fostering, and also both an adopter and adoptee.

According to figures from Adoption UK, 65 per cent of adoptive parents experience violence or aggression at the hands of their children

‘Social workers are not experts in trauma, they’re experts in risk and family life. What these families need is trauma-informed therapeutic, as well as practical, support, but once an adoption is finalised the children, and any issues they have, seem to be considered the responsibility of the adoptive parents.

‘Support is, technically, available, through regional adoption agencies, but there are often lengthy delays and misdirected guidance towards inappropriate solutions which perpetuate the problems.’ Naomi and Martin’s experience was sadly typical. The children, Tamsin and Joseph, had been taken into foster care aged one and two having suffered extreme neglect. Their mother abused drugs and alcohol, and they were not fed or washed. Their biological father was in prison for domestic violence.

Joseph was still a toddler when he started lashing out at them. Naturally, the couple turned to their social worker for guidance.

The only advice was to use ‘non-violent restraint’, such as changing the subject and distracting the child in a confrontational situation, and ‘natural consequences’ tactics i.e. leaving it to the child to work out the results of their actions themselves.

Blunt instruments indeed when you are being punched in the head or attacked with a baseball bat.

As one specialist adoption solicitor put it, with highly damaged children the approaches are like ‘applying an Elastoplast to an arterial wound’.

Unsurprisingly, things got worse. Their daughter’s violent outbursts began after she started secondary school.

Naomi believes this was due to her being dyslexic and on the autism spectrum – although she was never diagnosed. Again, the social workers were of little use.

Tamsin was 14 when, after a fall out over something Naomi struggles to recall, she attacked Martin so viciously, biting him and hitting him with a bat, that Naomi had no alternative but to call the police for help.

‘They arrested her, keeping her in a cell overnight, which was horrific, but they thought it would teach her a lesson,’ says Naomi. ‘Sadly, it didn’t, and it happened again, two weeks later.’

Then, one day she returned from a brief dog walk to find Joseph and Tamsin brutally attacking one another, close to the top of the staircase, ‘biting, scratching, kicking, hair pulling and spraying deodorant into each other’s faces’.

After trying, in vain, to separate them, in desperation Naomi called the police again. By the time officers arrived, the siblings had fled and Joseph was later found, sitting on a railway bridge, threatening to jump.

When behavioural issues manifest post-adoption – some of which can be genetic – parents are left to fend alone and blamed when the situation becomes unmanageable (file image)

Police managed to pull him to safety, and he was referred to CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services). The couple were told Joseph needed ‘dyadic developmental psychotherapy’, a specialist treatment for children who have been hurt or neglected in their early years, which would require both Naomi and Martin to attend weekly sessions.

This proved very difficult for Martin. As the family breadwinner, who now works in finance, he was unable to take time off work in the middle of the day. Though evening sessions were available, the couple’s request for these was ignored. Social workers were unsympathetic, and highly critical of him in reports.

Both children developed serious mental health problems, and would regularly self-harm, shutting themselves in the bathroom. At their wits’ end, the couple took the lock off the bathroom door – only to be told by social workers to replace it to ‘protect the children’s privacy’.

‘I was terrified one of them might die and begged social workers to get them urgent appointments with CAMHS, which still felt like our only hope, yet there seemed to be no urgency back then – though I understand they’ve had referrals now, after the adoption has broken down,’ recalls Naomi.

Everything came to a head at the beginning of the year when Tamsin had gone missing. Martin was out with Joseph in the car, scouring the streets, when he had what can only be described as a nervous breakdown. He later described how he’d started driving very quickly, feeling like he wanted to die.

‘Martin was full of remorse,’ says Naomi. ‘But we realised we were both so broken we could no longer cope and asked that the children be taken back into care.’

Initially the siblings were taken into care under a Section 20 order, a voluntary agreement between the adoptive parents and the local authority for them to provide temporary care, but now have a ‘full care order’, which means they will remain in local authority homes until they are 18.

The couple still see the children – last week Naomi met Tamsin to go shopping and took Joseph for tea and cake. On another occasion, Martin took Joseph to play pool. The last time the children visited the family home, for Sunday lunch, they stole £100 from a safe. ‘We miss them and still consider them our children,’ says Naomi.

‘And we don’t put any of the blame for what’s happened on them. They’ve developed a fight or flight response as a result of their early trauma and haven’t had the professional support they need. However, as much as we still love them both, it’s a relief they don’t live with us any more.’

One explanation for the rise in cases of children having to leave their adoptive home is the effects of widespread cuts in funding to local authorities and CAMHS, says Alison Woodhead, of Adoption UK. ‘Adopters often feel quite abandoned, not knowing what they’re entitled to or what support is out there.’

This was certainly the case for Stephan, a little boy who, together with his older sister Juliet, was adopted by Sophie Greenwood and her wife, Susie, a schoolteacher, in 2012, when they were aged two and three.

Both children were malnourished, covered in sores and fleas and so terrified of water that Sophie and Susie were unable to bath them, unless they climbed in too.

While Juliet developed normally, Stephan had abnormal brain development that could have been caused by exposure to toxins in the womb, as well as suspected foetal alcohol syndrome. He was diagnosed with autism, ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).

‘We wanted them to stay together, so we could all be a forever family,’ says Sophie. ‘However, we had no idea what a fight we had on our hands to get our son the support he needed.’ As a toddler, he was easy to pick up and distract, but as he grew bigger he grew increasingly violent – biting and kicking his parents and his sister.

Warned not to physically restrain him, Susie and Sophie would hold a kickboxing pad in front of them to soften the blows.

Eventually, when he was eight, they couldn’t cope any more.

‘A therapist, assigned by the local authority, agreed that our son needed a specialist residential school, but said the only way we’d secure one was to report any significant physically aggressive incidents to the council and the police, so there was a log.

‘We did this, and the local authority pushed back, placing both children on the child protection register under suspicion of ’emotional abuse’.’

Stephan moved to the residential school aged ten, leaving Juliet at home. In theory, this meant Susie was able to return to work as a teacher. However, she was now on record as being the mother of children ‘at risk’.

‘The fight for support and the shame just broke her,’ says Sophie. ‘She was so tired and constantly ruminating over the injustice of it all.’

One evening, in late 2022, Susie took her own life.

Sophie sobs as she recalls breaking the terrible news to their children — Susie’s death heaping further trauma on top of what they had already endured.

Juliet, 15, is developing normally, while Stephan still comes home regularly – but remains prone to lashing out. Although she cannot bear to imagine her life without her two children, Sophie admits that, had she and Susie known what lay ahead, they would have been unlikely to proceed with adoption.

Adoption specialist solicitor Nigel Priestley says the legal firm where he is a senior partner, Ridley & Hall in Yorkshire, is contacted by about 150 adoptive families in crisis a year.

‘Long gone are the days when most babies adopted came from teenagers, in mother and baby homes,’ says Nigel. ‘We have a whole host of children coming through who carry significant issues with them. Specialist support for these children costs local authorities a fortune and, over the last ten years, the services that provide support have been cut to the bone.’

Alison from Adoption UK stresses that this lack of funding is the issue, and that the devastating impact of adoption breakdown on the child should not be forgotten. ‘When adopted children and young people leave the adoptive family home prematurely it is devastating for all concerned, particularly the young person.

‘It’s almost always because they are let down – by adoption services, by mental health services and by the education system. Most adoptive families describe a constant battle to get the support their children and young people need. When children and young people do leave their adoptive family home prematurely, many return there. And many adopters with children and young people living away from home are still intimately involved in their lives and their care.’

As one mother, whose marriage didn’t survive after she and her husband adopted three traumatised, and later violent, siblings who had suffered terrible neglect and abuse, says: ‘I don’t blame the boys for how they behave – if I’d had their start in life, I’d no doubt struggle to control my emotions too. I blame the system for not giving them the help they needed. There should have been ongoing support in place from the get-go.’

Hundreds of devastated parents up and down the country, whose adoptions have been similarly disrupted, agree wholeheartedly.

- For support, visit the PATCH website at ourpatch.org.uk

- Names of children and parents have been changed.

Adopted children to have closer contact with birth families

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c3vl5w3zy2eo

Adopted children to have closer contact with birth families

Sanchia Berg and Katie Inman

BBC News

- Published 7 November 2024

Adopted children are likely to be allowed much closer contact with their birth families in the future as part of “seismic” changes recommended in a report published today. Some families say the changes are long overdue but others worry they may deter people from adopting. Angela Frazer-Wicks’ two sons were removed from her care and adopted in 2004, when they were aged five and one. She was in an abusive relationship and had problems with addiction and her mental health. By 2011 Angela had recovered, she was in a new relationship, and had a baby daughter. The local authority was not involved in her daughter’s care. Angela’s sons and their adoptive parents had stayed in touch with her writing letters and sending photos once or twice a year. But when the older of the two boys became a teenager, he told his adoptive mother he no longer wanted to write to his birth mother. Angela carried on sending cards, but heard nothing back for years. Then out of the blue, in 2020, Angela received an email from her eldest son. It turned out he had been trying to contact her, but the local authority had told him that wasn’t possible. Last month, Angela met her eldest son in person – it was the first time she had seen him for 20 years. “It was amazing for me,” Angela says, “even more so for my daughter – she’s waited her entire life to meet her brother.”

Adoption is the state’s most powerful intervention in family life. It is a permanent break between a child and their birth family, and alters the child’s identity forever. In law they are no longer the child of their birth parents, and most adopted children grow up without seeing or knowing any of their birth family. Around 3,000 children are adopted in England each year. It’s a process that must be authorised by judges in family courts, who set out the level of contact the child will have with their birth parents usually just letters, sent twice a year, via an intermediary. While adoption law has evolved over the years allowing children to know more about their history than they once did, in some ways, families say, adoption is still very much stuck in the past. Now a new report from a group set up by the most senior judge in the family court, external says wholesale reform of the system is needed. “Letterbox” contact between adopted children and birth families is outdated, the report says, instead recommending face-to-face contact where that is safe. The extremely detailed report is strongly supported by Sir Andrew McFarlane who says there is no need to change the law for this to happen. The report is likely to influence family court adoption hearings throughout England and Wales. Angela Frazer-Wicks describes her experience of adoption as a “life sentence without any right to appeal”.

As chair of trustees of the charity Family Rights Group, she is pleased mothers like her will have more chance to continue seeing their children after they have been adopted. “It’s a seismic shift,” Angela says. “It’s been such a long time coming. My hope is that we start to see just a bit more compassion towards birth families – they are so often seen as the problem.”

While meeting birth family can be very positive for some adopted children, face-to-face meetings aren’t good for all children in this position. When Cassie was adopted aged three, she constantly worried about the mother she’d been take away from. Out shopping with her adoptive parents Dee and John, Cassie would even ask if she could buy groceries for her birth mum. Dee was advised it would be reassuring for Cassie to meet her birth mother face-to-face. Their reunion, in a noisy contact centre, went well but the following day Cassie was very tired, pale and limp. Dee decided to take Cassie to the doctor, and by the time they arrived at the surgery Cassie was trembling and vomiting uncontrollably. But there was nothing physically wrong the doctor said Cassie was in shock. For nearly two years Cassie and Dee went to specialist therapy. Cassie still seemed to worry about her birth mother, and would try to call her on a toy telephone. Another meeting was arranged, in a quieter environment, with support. After that, Cassie, who is now aged 30, says she didn’t want to see her birth mother again. “I never felt a strong urge,” she says. “I had all the information about her.”

More reporting from family courts

With more recent adoptions, there is a new kind of risk. Children can trace their birth family online and some will go and meet them. That can lead to conflict with adoptive parents, even adoption breakdown. “The children become very emotionally mixed up,” says Sir Andrew McFarlane, the head of the Family Court in England and Wales.

“If you’re trying to work out who you are you in the world, and you have some memory of the family you lived with until you were four or five it’s almost natural to try and trace them and be in touch with them.”

Without expert help, this can have disastrous consequences. In 2021 one couple told the BBC it was “devastating” to see their two adopted sons turn against them and get drawn into crime, after they had been reunited with their birth family. There is no accurate data on how many adoptions break down. The charity Adoption UK has said it varies between 3% and 9%. Following a four-year review and consultation, the 170-page report published today says greater consideration should be given to whether adopted children “should have face-to-face contact with those who were significant to them before they were adopted”.

The report is intended as a review of the adoption process and a “catalyst for positive changes”.

Among the dozens of other recommendations are reforming the law on international adoption, and setting up a national register for court adoption records to make it easier for people to find their own files. The report also recommends dropping the term “celebration” for parents’ last visit to court with the child they are adopting. Many adoptive parents agree the current “letterbox” system of contact is not effective. In a 2022 survey, Adoption UK found that most prospective adopters believed that standardising direct contact would deter people from adopting, at a time when the number of people coming forward to adopt is in decline. But at the same time, it found that 70% of those looking to adopt believed that direct contact should be standard practice, if considered safe. Others think it could create further problems. Nigel Priestley is a specialist adoption solicitor and an adopter himself. He has seen the issues this contact can cause. “I think it’s enormously risky,” he says. “In my view there is a grave danger that if you once open Pandora’s Box shutting it will be impossible.”

A Department for Education spokesperson said the value of children growing up in a loving family “cannot be underestimated”. And for many children in care, “adoption makes this happen”.

“We know that adoption has a profound impact on everyone involved, and it’s vital that the child’s best interests are protected and remain at the heart of the process.”

Clarification 8 November 2024: This story has been amended following updated information supplied by Adoption UK

Delay and frustration in adoption law’s first year

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp3dx01v8x8o

Delay and frustration in adoption law’s first year

At a glance

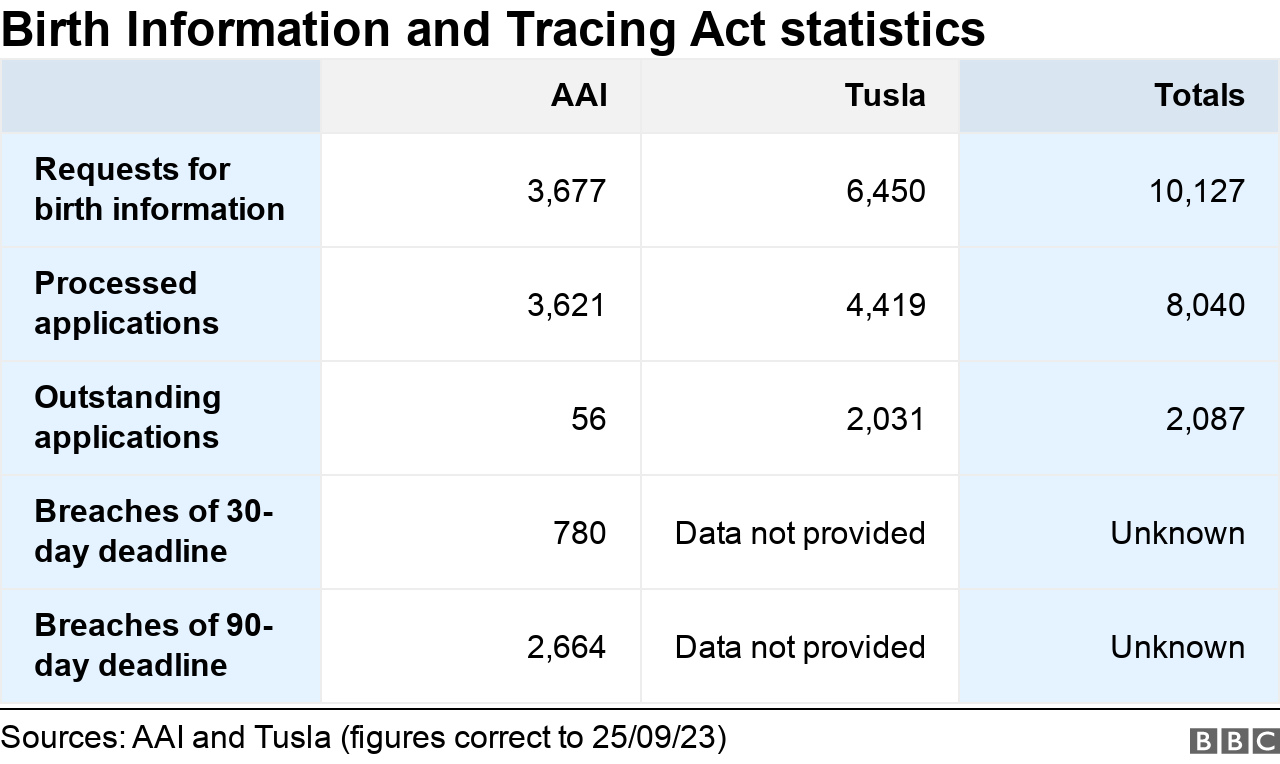

- More than 10,000 requests for adoptees’ birth records have been submitted during the first year of a new Irish law

- The authorities struggled to meet demand and missed legal deadlines

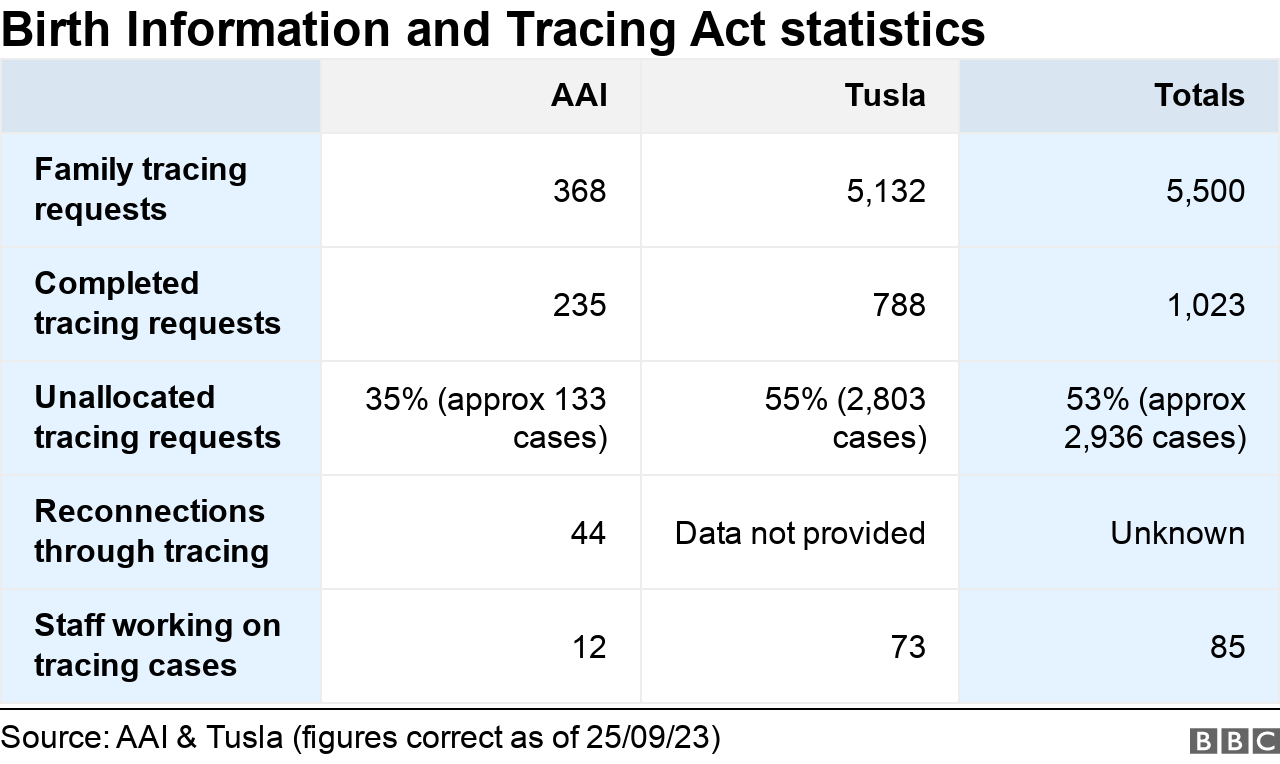

- A total of 5,500 requests were made to use a new family tracing service

- More than half (53%) of tracing requests are yet to be allocated to staff

Eimear Flanagan

BBC News NI

- Published3 October 2023

An Irish law that gave adopted people the right to access their birth records has led to more than 10,000 applications during its first year of operation.

The Birth Information and Tracing Act, external was designed to end much of the secrecy embedded in Ireland’s 70-year-old adoption system.

But for many adoptees waiting decades for answers about their early lives, the new procedures meant delays and frustration.

The legislation created a new family tracing service and throughout the year 5,500 requests to find relatives were submitted.

However, due to the complexity of some searches, 53% of tracing requests are yet to be allocated to staff.

“I am relying on a system that is working at a snail’s pace,” said Linda Southern, who is searching for her birth parents.

The 48-year-old Dubliner was adopted in 1975 at six weeks of age.

She spent her first 47 years not knowing her birth name nor the names of her mother and father.

That is because until 3 October 2022, Irish adoptees had no automatic right to see their own birth certificates, nor to know their biological parents’ identities.

The new law was supposed to give adoptees access to birth records within 30 days, or 90 days in complex cases.

Two organisations tasked with releasing records struggled to handle an early surge of applications.

The Adoption Authority of Ireland (AAI) and child and family agency Tusla both missed statutory deadlines.

“The initial surge led to wait times which would be frustrating and which we regret,” said AAI interim chief executive Colm O’Leary.

“When you’re starting off a process and you’re learning that records are held across various sources, it takes time to become familiar with all of the record types,” he explained.

A Tusla spokeswoman said “a significant portion of the applications are classified as complex which means they require more time”.

But adoptees argue authorities should have been better prepared.

“Surely, state bodies would have had a basic idea of the number of adoptees who would want to at least get their birth information,” said Ms Southern.

After initial delays, she received her own documents which – for the first time – revealed her original name and parents’ names.

However, she still needs help finding her biological family and spent the past year waiting for news.

“I don’t know if they will ever trace my birth mother or not.

“If they can’t, I should be told,” she said.

“They should have presumed the majority would want to trace – better to presume that too many people would wish to trace birth families than too few.”

‘Belfast baby’

Loraine Jackson had hoped her birth files might shed some light on her cross-border adoption.

She grew up in Dublin, with barely any information about her birth.

But in her early 40s, she found out she was actually a native of the United Kingdom, having been born to a single mother in Belfast in 1948.

Her parents died years before she could trace them.

When she spoke to BBC News NI last year, she expressed hope her files might reveal how or why she was taken across the border for adoption.

After months of waiting, a “fat package” arrived in the post which included an unredacted version of her adoption agreement.

For the first time, she saw her relatives’ signatures and finally found out who authorised her adoption.

“My birth mother had not been present at the signing. Her sister signed for her,” Ms Jackson explained.

She also expected her files would contain information about the standard of care she received in Bethany children’s home in Dublin.

But apart from a photocopy of her name in Bethany’s admission book, she was disappointed.

“The information just didn’t seem to be there. Whether records were not kept as well in those days, I don’t know.”

Although left with many unanswered questions, her maternal aunt’s role in her adoption was new information to her.

“It was definitely worthwhile doing, and I’d advise anyone who hasn’t applied yet to go for it.”

AAI staff received a wide range of feedback from adoptees about their birth files – from delight to disappointment to disbelief.

“A lot of people have said: ‘Is that it? Is there nothing else?'” Mr O’Leary said.

He acknowledged some adoptees were dismayed to learn that nothing more exists on file than details they already knew.

Others have received heavily censored documents.

“Sometimes the authority gets records that are already redacted prior to us getting them… we cannot unredact it,” Mr O’Leary explained.

He also said AAI staff can apply redactions themselves, in cases where personal information refers to a third party.

However, he added applicants can request a review if they believe files were “inappropriately redacted”.

The interim chief executive acknowledged the AAI’s 12 social workers have “significant” tracing workloads.

But he said tracing “is not a linear process” and adoptees often pause the search themselves to digest new information.

“You’re dealing with a very emotive situation,” Mr O’Leary said.

“People may initiate a trace, thinking that their birth mother would want to hear from them, and they have to take on board that the birth mother does not want contact.”

But the new law produced positive outcomes too – the AAI’s tracing service has facilitated 44 family reunions.

“Sometimes I’ll go to the kitchen and I’ll see a social worker taking out the fancy crockery and making tea” Mr O’Leary said.

“They’re bringing it into a room where a family is being reunited.”

He added that when staff help connect families “there is a sense of success, and of delivering on the legislation”.

The AAI’s backlog of birth record applications is almost cleared and by last week, just 56 were outstanding.

Tusla has a much larger backlog which it expects to clear by June 2024.

It said from1 September, all new applications are being processed “within statutory timelines”.

If you are affected by the issues raised in this story, help and support can be found at BBC Action Line.

‘I knew there was something missing from my life’: The incredible story of three siblings who met for the first time in their sixties after being given away for adoption to three different families

‘I knew there was something missing from my life’: The incredible story of three siblings who met for the first time in their sixties after being given away for adoption to three different families

Episode six of Long Lost Family airs on ITV1 and ITVX tonight at 9pm

By Emma Pryer

Published: 16:55, 25 August 2024 | Updated: 08:44, 26 August 2024

When Mary Arbuthnot opened a letter from her dying father, Richard, more than 20 years ago, she had no idea it would change the course of her life. The sealed, brown envelope with ‘Mary’ on the front contained some paperwork and a note, reading: ‘Alright Queen. If you want to find out any info, here are the numbers. Love always, Mum and Dad.’

One of the phone numbers her father had provided was for a Liverpool adoption agency a call to them began what turned out to be a long quest to find her birth family. The agency’s records revealed that Mary’s birth mother was an unmarried Irish woman called Rita O’Reilly, who had been living in London but for some reason travelled to Liverpool for Mary’s birth in 1965 and that Rita had also given birth to two other children, a girl born in 1960 and a boy born in 1962. Mary, from West Derby, a suburb of Liverpool, was stunned. ‘I’d known since I was seven that I was adopted as a ten week-old baby, but I’d had such a great childhood with my brother, who was also adopted, that I never thought any more of it.’

So happy was she, that she had often yearned for other siblings. Now she was left overwhelmed by the news she actually had two she’d never met. Named Bridget and George, they were born in London. And, like her, they had been adopted, each to a different family. Unusually, they shared the same father, an Irishman called Jim Melody. ‘I was so shocked. It was a strange feeling because I’ve had a happy life, but there was always this thing that something was missing,’ says Mary, 58.

Meeting her brother and sister, she felt, would make her life complete. That same year, 2002, she spoke to a counsellor at the Nugent Adoption agency, who was able to give her some more information about her birth parents and siblings. It threw up a mix of emotions. Mary had always imagined her birth mother as a vulnerable teenager, forced by poverty or family disapproval to give up her baby. ‘Back in the Sixties, it would have been hard under those circumstances,’ says Mary, 58.

Instead, she discovered that her mother was 34 when she had given birth to her and had already given two babies away. ‘That didn’t sit well with me. I’m not angry at all, I just can’t fathom how any woman can give a whole family away. She was offered help by the Church but still chose to give us away.’

For the first time, Mary began to have doubts about trying to find her brother and sister: would they even want to be found?

‘Did they know about me and, if so, why hadn’t they come searching?’ she says. ‘Part of me thought that if I started looking and they didn’t want to be involved, I’d be sorry.’

For the time being, Mary busy with her career as a hairdresser and her role as a mother to Stephanie, now 38, and Richard, now 30 put the search out of her mind. Then, three years later, her father died. That loss seemed to trigger an even more powerful longing for the siblings she had never met. She found herself glued to the heartbreaking stories of adoption and reunion on ITV’s Long Lost Family, the programme that reunites relatives separated by adoption. In 2022, after yet another tear-jerking episode and a full 20 years since her father had given her the letter Mary finally decided to take a chance. She filled out an application to the show and then, as life got busy, almost forgot about it. Five months later, she received an unexpected phone call. ‘It was one of the Long Lost Family team who wanted to ask some more questions. I nearly dropped the phone!’ she says.

Because she had her siblings’ dates of birth, the team was able to make a quick breakthrough. They found her brother George and sister Bridget who was now called Andrea. Not only were they both alive and well, but were living just 40 miles apart from one another, 240 miles south of Mary. In an upcoming episode of the series, co-host Davina McCall breaks the news to Mary at her home in Liverpool. ‘It was just unbelievable,’ Mary recalls. ‘It was a life-changing moment, that’s the only way I can explain it. I started shaking because even though I’d known about them, it was another thing to actually be told “we’ve found them”.’

George and Andrea, meanwhile, were dealing with their own sense of shock after each receiving a letter from Long Lost Family explaining they had a sister who was trying to trace them. Andrea Tovey, 64, a former civil servant from Gillingham in Kent, initially thought the letter was a scam. ‘I was a bit suspicious. It was just such a shock to get a letter saying my sister was wanting to find me when I never knew I had one,’ the mum of two admits.

It was even more of an ‘unbelievable, wonderful shock’ to be told that she also had a brother. Today, as the three of them speak, there is an undeniable ease and warmth between them. They fall into a casual, comfortable patter as if they’ve known each other for decades, not months. With similar laid-back demeanours and endearingly gentle laughs, only Mary’s soft Liverpudlian accent gives away the fact the trio didn’t grow up together.nnAs Mary jokingly cuts across from George as he proudly claims responsibility for the reunion he had been looking for his two sisters for more than four years and was just days away from finding them himself before Long Lost Family got in touch you can see they have already developed that unmistakable knack for jovial sibling bickering. They chuckle about the obvious physical similarities: ‘We are all very pale,’ laughs Mary, ‘and if you look at the shape of our eyes and mouths I think it’s the same’.

Unlike Mary, both George and Andrea were raised as only children. Born in Highgate, London, and raised in Gillingham, Andrea had always known she was adopted. Like Mary, she had a blissfully happy childhood, brought up principally by her father, Leonard, after her adoptive mother Betty died of cancer when she was just six. Andrea had pulled her birth records as a young adult, but as she was the first child to be born to Rita O’Reilly, there was no mention of a younger brother or sister. Life was busy and fulfilling and she decided not to chase after her parents in case they weren’t interested in meeting. Born in Hackney and raised in Loughton, Essex, George Buttwell, 62, had also known he was adopted as long as he could remember. Like his sisters, he had a happy childhood, leaving him with little urgency to uncover his past. In 1998, his wife, Lesley, saw a programme about accessing adoption records, which piqued steel fixer George’s interest. He applied for his adoption paperwork and original birth certificate, which provided brief details about his birth parents. But it was really only years later in 2019 that his search got going. George’s youngest daughter, Lindsey, 34, bought him a DNA test as a gift. The results opened a new chapter, throwing up relatives he never knew he had in Ireland and London. He began to discover more about his past than he had ever imagined. George’s DNA test linked him to a second cousin in Ireland and through him and another member of his extended family, he heard he had two sisters for the first time. ‘Knowing that, I became determined to find them,’ says the father of three.

He then decided to explore a hunch that his sisters might have been born at the same Catholic nursing home in London as him. St Margaret’s no longer existed, but he was told he might be able to find out more about his sisters through the Catholic Children’s Society in Westminster. Its records contained the full names and dates of birth for his sisters. His local council adoption service agreed to contact his sisters on his behalf and was just doing some final legal checks when the letter arrived from Long Lost Family. ‘I’d been looking for four years by that stage. I told [the adoption service] to call off the search. It was amazing news but perhaps not as much of a surprise as it was to Andrea, who didn’t know about either of us.’

Last November, the three siblings finally came face-to-face in a Liverpool hotel in emotional scenes which will be broadcast tonight. As Davina explains as they wait to meet: ‘It is very rare for Long Lost Family to find and bring together three full siblings all of whom until today have been complete strangers to one another.’

Andrea was first in the room; her heart in her mouth. ‘It actually felt like quite a while before they came in and I started getting emotional before,’ she recalls. ‘It was something I’d never believed could happen after all this time but it was so nice. We held hands as we talked and we just seemed to get on straight away.’

George agrees. ‘It did feel like we were all family. You could feel that straight away that we’ve got this thing in common, no matter how far we’ve drifted.’

Now, though, the sibling bond appears to be growing stronger with every passing month. They have an official family WhatsApp Group called O’Reilly Melody after the surnames of their birth parents. In January, less than two months after the show, they came together again at George’s Essex home, where a picture of the three of them now takes pride of place in the living room. A second reunion followed in June, with a pub lunch in London and another trip to George’s house to share notes on their histories and meet extended family. Just this week, George’s daughter Sarah, 38, flew in from Spain and Andrea was there to meet her. Small things mean a lot: for Mary, it’s been a thrill to send birthday and Christmas cards to her brother and sister for the very first time. The growing bond feels so natural that Mary has even taken to cutting Andrea’s hair. ‘Every time I’ve seen her she’s blow-dried my hair and last time she actually cut it. I’ve never looked so glamorous,’ smiles Andrea.

But for all the joy of getting to know one another (Andrea even jokes she shares the same love for the TV detective, Columbo, as George) there is sadness for the missed years they could have had together. ‘I know that my parents would have adopted the other two if they’d have known and we could have all been together, as we should have been,’ says Mary.

The siblings have discovered that Jim Melody passed away around 20 years ago and Rita O’Reilly around ten years later. As they were unmarried, Jim was buried in Ireland and Rita in Finchley, North London. From what they have gathered from relatives, the siblings understand that Rita and Jim lived together on and off for 40 years, but the real nature of their relationship remains a mystery: the pair have taken to the grave many unanswered questions for Mary, Andrea and George. ‘For the time they were living in, for their background, it would have made a lot of sense to get married, so why didn’t they?, George, who has visited his mother’s grave, has often wondered. Why did their mother have them adopted, and to different families?

And why, when Rita and Jim appeared to travel from Dublin to London together, did Rita keep leaving their London address and flitting to different areas?

For now at least, the unresolved questions are overshadowed by the joy of finding one another. ‘I’ve got ideas of what I’d like to do if I get to the point of retiring, but this has given me this extra positive feeling. It’s this happy unknown future now and there’s already this genuine love there with us,’ says Andrea.

‘It’s a feeling you can’t really describe because it’s something I’ve never experienced before,’ says Mary. ‘It was like I’d already known them forever.’

Episode six of Long Lost Family airs on ITV1 and ITVX on August 25th, at 9pm

Why is abortion illegal???

“Why is abortion illegal??? In my opinion all birth mothers who gave up children WILLINGLY belong in jail. I would rather have been aborted. This existence of not being apart of two families and being unable to have children of my own is unbearable.”

This is a post on one of the adoption related groups I belong too on Facebook which really got my back up. I have been a member of various adoption groups and forums since late 2004 and am saddened that education is still as bad now as it was 16 years ago. The problem is this person knows exactly what they are getting at but from the point of view of a mother, I’m not the only one, that ‘willingly’ gave up my son as that’s how the adoption industry portrays. I do know there are mothers who really didn’t want their children and haven’t wanted reunion but they are a minority. My point is that I’m still willing to speak out that willing surrendering of a child isn’t that common and people should educate themselves. From my son’s point of view he knows what it’s like to be rejected by his father and to a certain extent by a family member.

The reality is we didn’t willingly give our children up, they were taken away / stolen because of the greed of adoption agencies and our mothers didn’t want us to be single mothers / it was shameful to have a baby out of wedlock.

Of course these days there is a big difference between the UK and the US these days as private adoption stopped in the UK. With mothers having access to benefits saw the decline of infant adoption in the UK although forced adoption still continues – forced adoptions are illegal but extremely difficult for parents to stop.

I shouldn’t have responded to the post as I still get attacked for telling the truth because people accuse me of not reading properly, in denial that I ‘chose’ adoption, I regret the ‘decision’ and so on, My response was because of the amount of people who haven’t believed the truth over the years and they will never understand the pain they cause.

“….. …. I am one of those mothers who you reduce to the act of giving birth. I, like many other mothers, chose life for my son, I wanted to raise him but he was stolen from me because my mother didn’t want a daughter to be a single mother. It was harder to adopt babies by the time my son was born as mothers knew their rights. I lost my son because my mother and the adoption agency lied to me and it was 23 years later I found out the truth. I don’t even know who signed the Consent to Surrender when he was 6 weeks old as it was very conveniently lost yet I was able to have all the other relevant paperwork post reunion which should have been given to me 23 years previously. None of the information was given by me and the only truth was a description of me and his father. It was that bad that there was two completely different jobs down for his father but he had never done either of them. Instead of spewing out your ignorance try educating yourself.”

Maybe I should have made myself crystal clear that to the world I ‘willingly’ gave my son up and been more polite at the end but I’m tired of being polite. I’m tired of people coming across as ignorant, not educating or show that they have educated themselves. I’m tired of mothers are made out to willingly getting rid of their children. On the other hand he could have been more specific – how do I know if he knows that not all adoptions will done willingly.

The response I got back was from a female:

” ….. I re-read the original post. No where does it say that all mothers gave their babies up willingly, only those that did should go to jail. Adoptees have the right to their feelings on this.”

Disliked adoption phrases Part Two

Over the years family (my in-laws) and friends who found out, I had a son and we had connected have made ‘uneducated’ comments. I got sick to death of the ‘how wonderful’ it was that we reunited comments in particular. Other comments have been ‘it was for the best’, ‘you were young’ and so on which, in turn, has meant that I have had to be extremely calm and explain that I could have raised my son. I shouldn’t have to explain myself but it’s the only way to explain the dark side of adoption.

It’s been far easier to explain to the adoption community of the dark side of adoption. I’ve had my battles and it’s been worth me standing my ground.

I hate it when anybody says ‘it was God’s plan’ because it’s never in God’s plan that newborns are adopted. If that was true every parent would be surrendering their baby for adoption and adopting somebody else’s baby. It is as bad as saying God put a baby in another woman’s womb just so a couple can adopt him or her.

I remember my son asking me not to say anything negative about his adopters. My response back was on the lines of ‘Why would I as I don’t know them?’

Over the years I have been irritated by the DNA/nature doesn’t matter but nurture does and even a few adoptees have said that to me. If they don’t matter why do mothers feel profound feelings of pain and loss, why do adoptees want to know who they look like?

I’ve been told a few times that I’m not a mother as I didn’t raise my son with my mother being one of them. She and the others didn’t ‘get it’ that

Thankfully these days I don’t get so involved in adoption in real life online unless I feel up to it. It’s really not worth the aggravation, arguments, bad feelings or the effect on it has on my mental health.